Recent times have been marked by fear and uncertainty: wars, the rise of artificial intelligence, and the restructuring of the legal status quo. Academic institutions have gradually abandoned the humanities.

In recent years, reports from universities and cultural institutions have confirmed what many feared: the humanities are being steadily abandoned. According to the World Humanities Report (UC Berkeley, 2024), public and private disinvestment has made humanistic disciplines “more vulnerable than ever.” In the United Kingdom, the share of students choosing humanities subjects has dropped from nearly 60 percent in 2003 to barely 38 percent in 2021–22. Across the Atlantic, numerous U.S. state universities are cutting programs in languages, philosophy, and literature in favor of more “economically oriented” fields. As writer and scholar Adam Walker recently observed, “while the right emptied the humanities of value by reducing education to utility, the left emptied them of meaning by reducing texts to ideology.” The result is an academy that no longer cultivates the human being but rather the technician and the partisan—forgetting that the purpose of the humanities has never been productivity but learning.

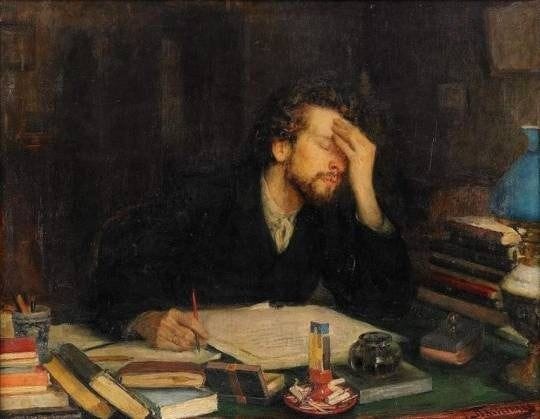

We are encouraged instead to practice a “self-knowledge method,” a parallel curriculum that invites us to become autodidacts—gathering resources, reading, and researching whatever sparks our curiosity.

The erosion of the humanities has consequences far beyond the university. When the arts, philosophy, and history retreat from education, societies lose their ability to think critically and to deliberate together. As Martha Nussbaum warned, “democracies need citizens who can think for themselves rather than defer blindly to authority.” Yet today, the decline of humanistic study has produced a generation trained to process data but not to interpret experience. Culture becomes entertainment, debate turns into noise, and language loses its moral precision. The gap widens between those who learn how to code and those who still learn why we create. Without the humanities, imagination and empathy shrink, and the public sphere disintegrates into factions of outrage. What remains is efficiency without meaning, productivity without purpose—a civilization that knows how to function but not how to live.

And yet, amid this apparent decay, something stirs. The sense is unmistakable: a new Renaissance may be coming.

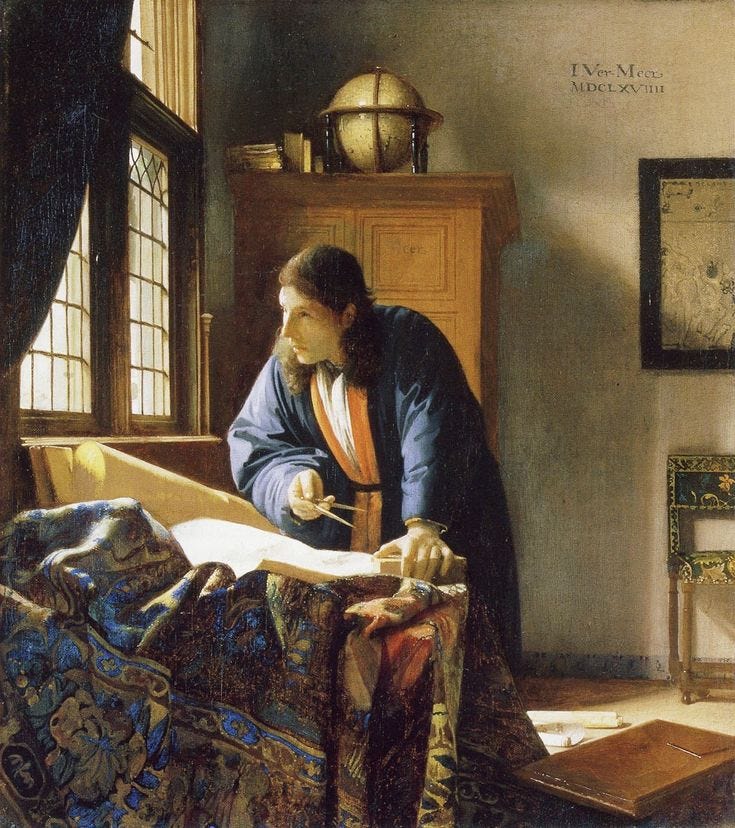

History teaches that every age of collapse conceals the seed of renewal. When a movement stretches too far and endangers what is essential to human nature, it provokes rebirth. The Italian Renaissance arose after centuries of scholastic rigidity; the Romantic revival followed the mechanization of life during the Industrial Revolution. In both cases, exhaustion gave way to imagination. The pattern repeats today. Our universities, like the medieval academies of Paris and Bologna, are weary of meaning—fragmented into jargon and ideology. But renewal rarely begins within institutions. Between 1390 and 1570, after nearly ten centuries of Church dominance over knowledge, the desire for restoration awakened—the longing to recover what had been forgotten. Marsilio Ficino’s “Florentine Academy” flourished precisely because the official universities had become sterile. It was in private rooms, among translators, poets, and dreamers, that a new vision of humanity was born. The same may be happening now: in independent journals, online salons, and circles of self-taught thinkers. Every renaissance begins when a few refuse to let wonder die. And once again, wonder seems to be stirring.

It reminds me of Proust’s récit: a single, happy accident awakens a whole new world, revives what once was cherished. The printing press spread knowledge as never before, and creativity was no longer bounded. “Homo Universalis” embodied the ideal: science, art, and the very act of being coexisted as one.

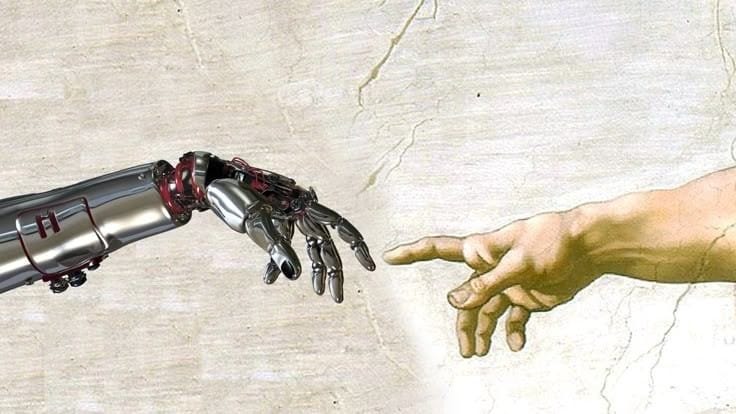

Of course, we should not romanticize the past. Yet I cannot help but admire the spirit of renewal that each Renaissance has carried. Today, amid chaos and algorithm, I begin to sense it again. The growth of technology, of artificial intelligence, of virtual worlds—these forces reveal how far we have come, and how far we have drifted. Perhaps from a more natural state.

What, then, is the role of the humanities when they seem to matter so little? It’s up to us. Perhaps precisely now, at the height of a society dissolving into zeroes and ones, we will turn back to them. Perhaps not. Who knows whether society will find any use for someone educated in literature or art twenty years from now. We will have to face ourselves again, measuring not by what we produce but by who we are.

In art, this transformation is already visible. A new discipline is emerging: the ethics of art. What better moment to reflect on it than when machines attempt to reproduce what we once thought irreducibly human?

Everything today feels blurred, unsettled. Yet every experiment requires discomfort. To move forward, we must once again ask the ancient question: what does it mean to be human?

And yet, in this apparent twilight, small lights are appearing. Cultural exhaustion has always been the prelude to renewal. After the triumph of the artificial comes the nostalgia for the real. The more algorithms mimic thought, the more urgently we ask what it means to think. Across the world, students and readers are turning again to philosophy, art, and history—not as luxury, but as survival. Universities like Harvard, Yale, and NYU are beginning to reconnect scholarship with public life through new Public Humanities projects, while countless independent writers and educators form digital circles reminiscent of Ficino’s Florentine Academy. These movements suggest that the next renaissance will not begin in marble halls but in living rooms and on screens, wherever a mind dares to wonder again. Perhaps the machines will teach us, by imitation, what only we can do by nature: to imagine, to discern, to care. When the noise subsides, the quiet work of the spirit will remain. And from that silence, the fire will start once more.

And to ask it well, we must turn our gaze to the past. Day by day, more people begin to touch upon this intuition—adding, even with small sparks, fuel to the fire.

The Renaissance fire.

Thanks for reading.

Thank you for this! I really hope that you're right in your tentative optimism.